One of the lessons from the Biden Administration is how much consumers hate inflation even when their wages keep up.

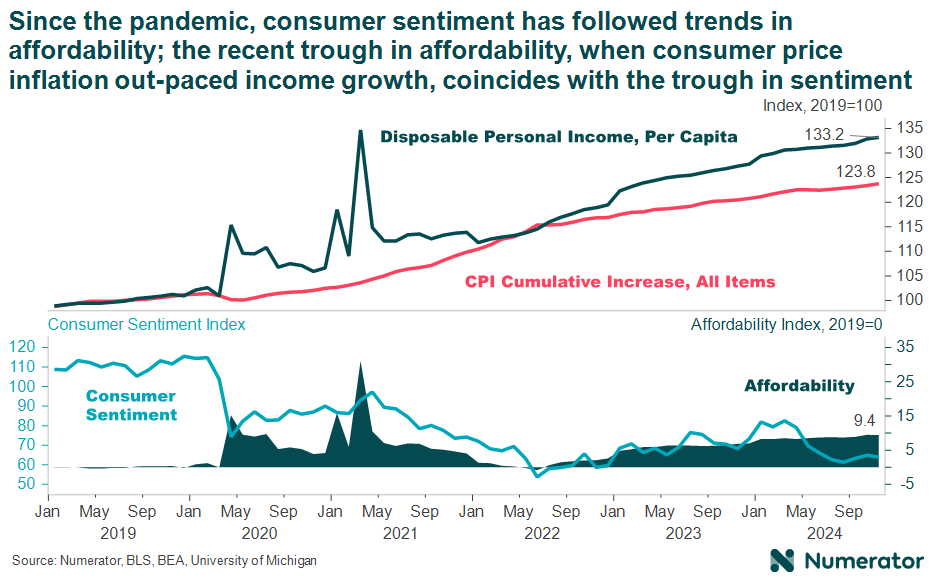

Since the pandemic, consumer sentiment has closely followed trends in affordability. When government programs boosted affordability early in the pandemic, sentiment increased. As inflation eroded purchasing power, sentiment declined. The trough in sentiment coincides with the trough in affordability in June 2022. For the average consumer, affordability is now up 9.4% versus 2019 because employment and income growth has more than made up for the erosion of purchasing power due to inflation.

When we look at what consumers are buying in stores and online using Numerator data, consumers from all income groups are buying more today than they were in 2018, even after adjusting for inflation.[1] By this measure, consumers should be better-off.

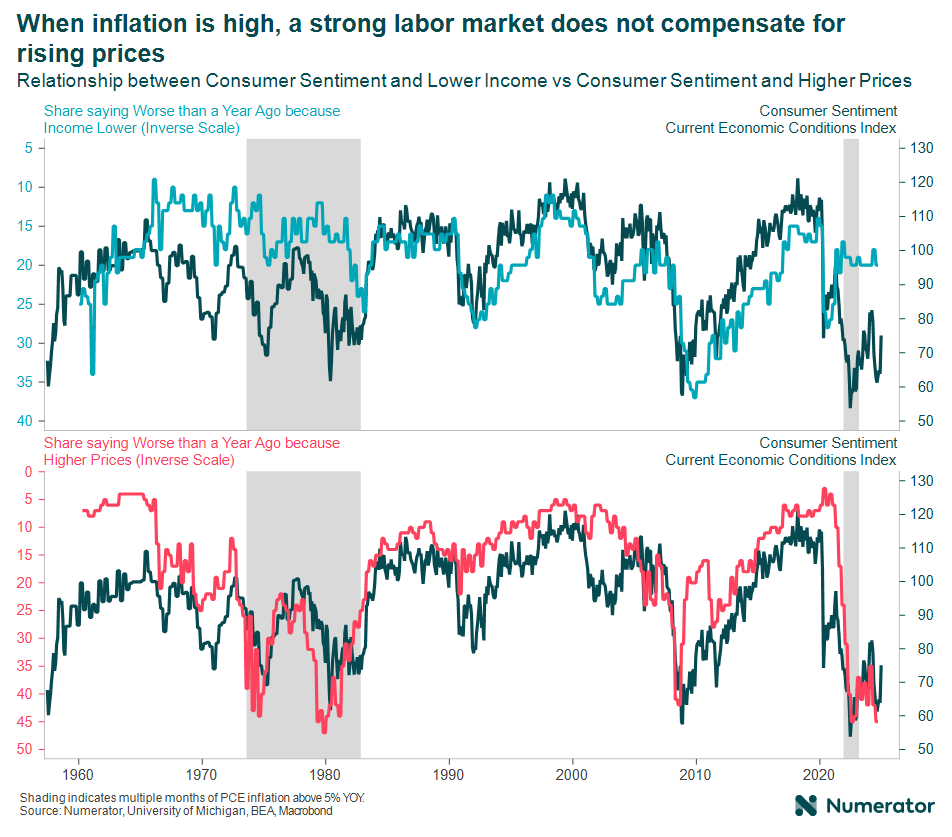

In University of Michigan surveys, whenever inflation is high, consumers say they are more likely to be doing worse because of high prices, despite also saying they are less likely to be doing worse because the labor market is strong. What dominates during inflationary episodes are concerns about inflation, not concerns about the labor market. Policymakers should be aware of this trade-off: given the choice between high inflation but a stronger labor market or low inflation but a weaker labor market, consumers seem to prefer the low inflation and weaker labor market option. A strong labor market does not seem to compensate for high inflation.

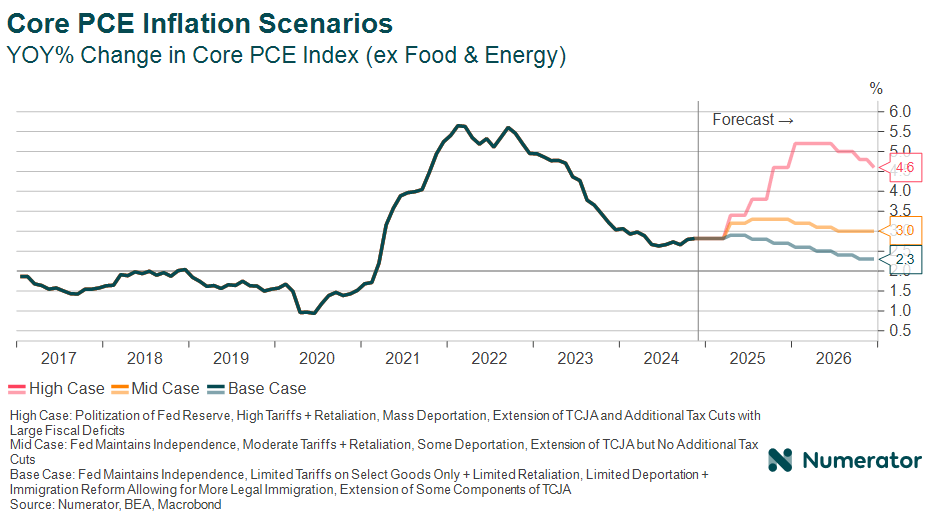

Will the policies of the Trump Administration reignite inflation? We examine three scenarios:

- High Case: In the high inflation case, the Federal Reserve loses independence. Threats to replace the Fed Chair with an accommodating political appointee or political pressure on the Fed’s rate decisions can be enough to de-anchor inflation expectations. We have seen the dangers of politicizing monetary policy in US history and in emerging market economies; doing so would be destabilizing to the US economy. The high case also features across-the-board tariffs, retaliation from other countries, mass deportations, an extension of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), additional tax cuts, and higher fiscal deficits. Tariffs and mass deportations constrain supply and raise prices in critical sectors. Additional tax cuts boost demand. The result is another burst of inflation.

- Mid Case: In the mid inflation case, the Fed retains its independence and credibility, which allows it to keep inflation expectations well-anchored. Moderate tariffs and some deportations lead to supply constraints and higher prices but less than in the high case. The extension of the TCJA does not lead to any changes in consumer demand. The result is a slight pick-up in inflation due to one-off supply constraints and to a lessening of import competition.

- Base Case: In the base inflation case, we see limited pick-up in inflation due to targeted tariffs. Reforms to immigration maintain a sufficient inflow of workers to prevent labor shortages in key sectors. Some components of the TCJA are extended but fiscal deficits are lower than in the mid and high case.

While some of the stated objectives of tariffs and deportations are to bring back jobs for American workers, the labor market is already strong. To the extent these policies reignite inflation, consumers have signaled they hate inflation – even when the labor market is strong – and they vote accordingly.

[1] For additional details, please see: Hoke, Sinem Hacioglu, Leo Feler, and Jack Chylak (2024). “A Better Way of Understanding the US Consumer: Decomposing Retail Sales by Household Income,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 11, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3611.